Wrestling Heritage welcomes memories, further information and corrections.

The legacy of the Second World War remained five years after the cessation of hostilities. Derelict sites and un-repaired bomb damaged buildings were still features of the larger towns and cities. Prime Minister Clement Atlee led the Labour government to re-election with a majority of eighteen over the Conservatives, but with one seat fewer than all other parties combined. The Labour vote of 46% would be unheard of today but contrasted sharply with the 99.7% voted received by the communists in the first East German elections, admittedly under very different electoral conditions. Uruguay were also winners, of the 1950 World Cup, beating Brazil in the final. In the same tournament England were humiliated, losing 1-0 to the USA.

The press gave column inches to boxer “Gorgeous Gael” Jack Doyle as he prepared for his wrestling debut, a February 7th match against Martin Bucht at Harringay Stadium.

The tournament was promoted by Atholl Oakeley, under his British Wrestling Association banner. Oakeley was trying to revive his pre war wrestling business, presenting lavish shows using his International Catch as Catch Can rules and not the Lord Mountevans style. It was claimed nine and a half thousand fans packed Harringay Stadium, paying between 3/6 and three guineas. A fanfare of trumpets sounded, and was repeated again and again before Doyle made a belated entrance, resplendent in a white and green satin dressing gown, white shorts embroidered with his initials. The entrance of Bucht may well have disappointed many fans. Here was a man said to be “The Human Gorilla” despite being reportedly shorter and lighter than Doyle, and not only that but he turned out to be a familiar figure to fans of the 1930s, having wrestled in Britain extensively under the name Padvo Peltonin.

As was to be expected the match did little for the credentials of professional wrestling. Doyle was mostly occupied through the first round being thrown around the ring and stretched by Bucht. It seemed to be going the same way in the second until a sudden flurry of activity gave hope for the Gorgeous Gael, only to be extinguished by Bucht pinning him to take a fall.

Could the Gorgeous Gael survive against the Human Gorilla? This is wrestling, of course he could. Round three began and Doyle rushed from his corner, felling Bucht with a forearm smash. Followed by a second as Bucht rose from the mat. And a third to finish off the Gorilla. Who would have believed it? The count of the referee was the signal for the pipers to return.

Extravagant shows such as this were not the norm, most fans happily paying a few bob to watch the sort of balanced four match tournament familiar to fans until the end of the 1980s.

It wasn’t just the fans disgruntled by the Harringay appearance of Doyle. Doyle was neither a member of the British Wrestling promoters Association or the Wrestling Federation of Great Britain. Programmes in WFGB halls stated: “Doyle, glamour boy of boxing has, at the time of writing, not been granted a licence by the Wrestling Federation. Such being the case no licenced wrestler will be allowed to appear on the same programme at Harringay as Doyle. If he does, the wrestler will be automatically suspended, and the question of his licence being automatically suspended will be considered by the Federation.”

An unholy alliance between the WFGB and the BWPA seemed too good to be true. The BWPA agreed to employ only Federation men and pay £1 from each of their tournaments towards the BWPA benevolent fund. As it turned out the WFGB claimed no contributions were received and at the committee meeting of November 5th, 1950, the WFGB withdrew their recognition of the BWPA members. Two years later members of the BWPA would go on on to form Joint Promotions, intent on restricting the rights of the wrestlers working for them.

Six months earlier, in June, promoter Norman Morrell had criticised the Wrestling Federation in the pages of the Yorkshire Post. Morrell booked Lord James Blears to wrestle Sandy Orford on one of his shows and had been told by the Wrestling Federation the match could not take place because Blears had been refused a licence to wrestle in this country. Morrell was quoted, “It appears that the Federation are trying to enforce a Trade Union closed shop. This is unheard of so far as competitive sports are concerned…. “ which is all a bit ironic in view of the part Norman was to play in the setting up of Joint Promotions just two years later.

All was not well in Dundee, where wrestling had been held at the Caird Hall since 1936, regularly drawing attendance of 3,000 fans. The Corporation Police Committee instructed the town clerk to write to the promoter, John Owens, expressing their disapproval of an incident at the hall. Apparently wrestler George Clark had thrown both his opponent and the referee from the ring and then pursued the contest amongst the crowd for about thirty seconds. The concern was that members of the audience could have become involved and injured, though one member of the committee was reported to have said that anyone attending a wrestling show deserved what they got. The Police Committee were reassured that the referee had made a full report of the incident to the Wrestling Board of Control. And they thought the fans were gullible!

The number of wrestling tournaments was continuing to expand with new towns being introduced to the sport. Professional wrestling made it’s post war debut at the Spa Theatre Bridlington, with members of the town council in attendance to make sure all was above board and to consider sanctioning further shows. Councillors of Bury St Edmunds also agreed to allow wrestling after turning down requests on previous occasions. One councillor argued that “There was wrestling and wrestling,” going on to say the type to be staged by these particular promoters was the type acceptable at the Olympic Games. So gullibility wasn’t limited to the Dundee police.

Most of these shows were presented by members of the Wrestling Federation of Geat Britain and the British Wrestling Promoters Association: Norman Morrell , George De Relwyskow, Ted Beresford, Arthur Wright and Dale-Martin Promotions.

The local paper reported that 2,000 people enjoyed a four match wrestling tournament inside a big top at Beacon Park, with hundreds more turned away. The main bout saw Bulldog Bill Garnon knock out Harry Brooks, whilst at the bottom of the bill a speedy and classy Mick McManus drew with Ken Joyce.

Wrestlers Stanislaus Zbysko and Mike Mazurki were in Britain filming “The Night and The City.” Richard Widmark starred in the film as Harry Fabian, a scheming wrestling promoter, whose over ambitious plans and greed led only to his own downfall. The film received mixed reviews for it’s gritty realism with critic Elizabeth Winters writing “Some of the wrestling scenes are very chilling,” and C.A. Lejeune, who disliked the film, writing, “There is one outstandingly good piece of work in all this nonsense; a performance by Zbyskow, the veteran wrestler….many were the appreciative nods from the elder sportsmen in the audience.” Another film doing the rounds was “Alias the Champ,” which starred American wrestler Gorgeous George.

George Hackenschmidt, 74 years old, and living in London, became a naturalised Briton, forty years after his first application had been turned down.

Irish wrestler Michael Casey appeared at a Wrexham court martial charged with being a deserter from the British army. Casey said he was an Irish citizen who did not want to join the British army and had returned to Ireland.

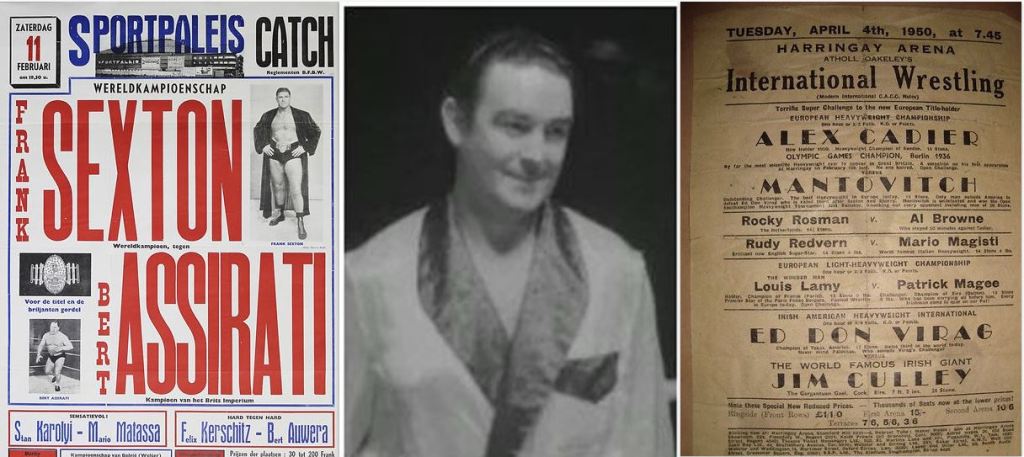

British heavyweight champion Bert Assirati popped over to Antwerp in February to challenge a World heavyweight Champion, Frank Sexton, wrestling a 60 minute draw.

British promoters continued to attract overseas wrestlers to our shores, and amongst those visiting Britain in 1950 we can include Chief Thunderbird, Bill Verna, Bob McMasters, Rene Bukovac, Pat Curry, Felix Kerschitz, Martin Bucht and Leo Demetral.

Without quite as much continental blood as he claimed was the veteran Izzy van Dutz, still wrestling and well into his twilight years. The Dutchman had risen to fame with promoter Atholl Oakeley in the all-in days and was still making occasional appearances. A short conversation with Izzy soon revealed that his origins were more associated with south London than south Holland. British through and through were the Pye family. Dirty Jack had now been joined in the ring by his son, Dominic.

The British wrestling business was continuing on its road to recovery. Five years after the end of the war fans were back in the habit of going to the wrestling on a regular basis. The foundations were being laid for the success of the sixties.