Wrestling Heritage welcomes memories, further information and corrections.

For only the second time in British history a state funeral was accorded to a non-royal as Sir Winston Churchill’s body passed memorably along the River Thames.

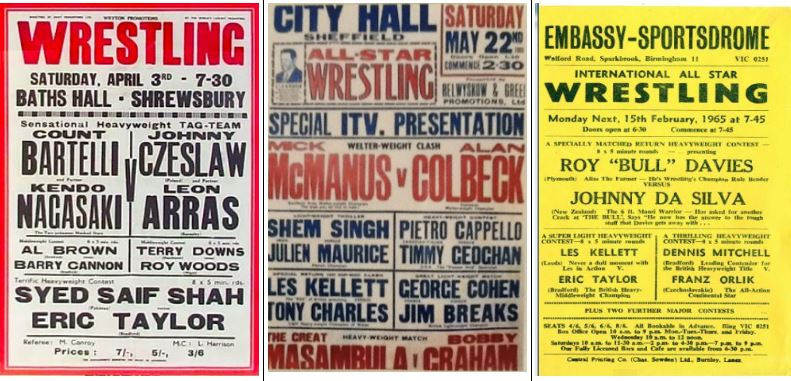

On the wrestling front, 1965 will forever stand out as the final year of competition between Paul Lincoln Promotions and Joint Promotions. Lincoln’s colourful bills and even more colourful heavyweight stars such as Ski Hi Lee, The Wild Man of Borneo and the man himself, Doctor Death, right, managed to make a serious impact on the wrestling scene nationwide and in spite of a lack of any television coverage.

Quite to what extent the two organisations were in conflict we cannot say with any great certainty, but the signs were there that 1965 saw the peak of whatever rivalry there was, with the two offering bills in rival venues in the same towns, and at times, as happened for example in Southend-on-Sea, the same night. Joint Promotions struck out at their rival, denouncing bills with animals and women through their official mouthpieces, wrestling programmes and The Wrestler magazine.

This Mods and Rockers style feud of the balmy mid-sixties summer must also have come to a head in some way because a few short months later the two organisations would merge, indicating that healing or selling out must have been taken place during the autumn. All we have for now are these outward signs of fire then fusion, and we continue on our Wrestling Heritage quest to unearth the true circumstances of the merger.

Whatever the politics, 1965 can justifiably lay claim to being the very highpoint of the Golden Years of Wrestling we describe, with the two well organised rival organisations in full flow, each trying to outdo the other, with only the fans benefiting. Not to mention many other independent promotions, where for example the Undertakers continued their in-ring mayhem oblivious to the year’s abolition of the Death Penalty.

It was also the first full year of wrestling’s inclusion in World of Sport, a position the whole business worked hard to maintain. Exciting international stars were brought in to give the impression of a truly competitive sport. Italian Nicolas Priore, France’s Vicomte Joel De Noirbreuil and Dan Boukard, Musa the Turk, and even Congo’s N’Boa the Snakeman all made televised appearances.

Another American made his small screen début at the very end of the year, The Masked Outlaw sensationally demobilising Steve Viedor. And yet another had tried to demobilise 007 on the big screen. Harold Sakata, known to fans as The Great Togo, left, was still active in the ring at the start of the year before the impact of his Goldfinger role as Oddjob would whisk him away from British rings for good. Purely coincidentally, by the way, the arrival of The Outlaw had come just after the final appearances of Canadian heavyweight, Gordon Nelson.

Back from Lincoln rings rather mysteriously a year before the rivalry ended were the Cortez brothers, Peter and Jon. Joint Promotions had been offering plenty of expensive heavyweight tag bouts, seemingly to compete head-to-head with Paul Lincoln, but these lightweight flyers proved themselves to be a leading team as tag wrestling captivated the nation, and hitherto undercarders found their places in main events. Also “coming over” early was Brian Craig-Radcliffe, better known to fans as The Society Boy.

Amongst the opponents for the Cortez brothers were another pair of siblings with the Maltese Borg Twins making their professional débuts. And northern tag team The Black Diamonds gradually changed shape as Sheffield’s Eric Cutler started in 1965 to replace John Foley alongside Abe Ginsberg.

Britain also enjoyed its final visit from arguably the finest continental of them all, Horst Hoffman. Coming in for the first time on the other hand were a couple of 6’6” giants: Jan Wilko from Johannesberg carried all before him and left British fans wanting more; and Greek Spiros Arion, who would return to kick up an even greater stir some 15 years later. Add the intriguing French masked man, Le Bourreau de Béthune, who was also active on Devereaux Promotions bills through the early months of the year though billed as The Executioner of Béthune, left, and 1965 just sparkles with talent and excitement.

Royal Albert Hall bills continued to represent the pinnacle of the sport, and a young Brian Maxine stepped into the main event limelight making a great impact against a Mick McManus at the peak of his powers. They reproduced their work on television later in the year and in halls nationwide. Of the many international wrestlers brought over by enthusiastic and capable matchmakers, perhaps the appearance of former legitimate World Heavyweight Champion Eduardo Carpentier was the highlight. He was held to a draw by Shipley’s Geoff Portz.

The tv producers strove in the mid-sixties to make wrestling meaningful, and in the climax to a well organised knockout tournament held over several months, Mike Bennett defeated Vento Castello to claim the Television Trophy. Such was the level of this event, perhaps hard to imagine for fans who grew up in the unbelievability of the post-1975 era, that Olympic Gold medallist and golden girl, the 1964 Sports Personality of the Year, long-jumper Mary Rand, graced the ring to award the trophy.

Such was the growing popularity of wrestling that the BBC took a small, tentative step at broadcasting the sport. BBC1 showed a single Paul Lincoln tournament in May, 1965, in which Jim Armstrong beat Frenchman Edouardo Carpentier in the main event. In January a wrestling show had been piloted on BBC2, again using independent promoters and their wrestlers. Having tipped their toe in the water it was quickly removed and the BBC never regularly broadcast professional wrestling.

Wrestling really did have a stranglehold on independent television in its fight against the BBC, and coverage extended beyond the in-ring entertainment. Multi-talented World of Sport presenter Eamonn Andrews also hosted the early evening talk show of the sixties. See him right alongside another wrestler who would also make it in tv comedy seven years later, Paul Luty. When Mick McManus and Jackie Pallo were scheduled to appear, McManus made extensive complaints and refused to sit with his rival.

Now, this was all great controversial stuff but the myterious fact is that in this sandwich year between McManus versus Pallo II of 1963 and McManus versus Pallo III of 1967, the pair did not clash. We have far too much respect for the shrewd promoters of the day to suggest any opportunities were wasted, but it is not immediately clear why such rivalry was hyped up over so long without quicker box office fruition. We can only conclude that the dormant rivalry was at such a level as to be PR for the business as a whole.

In terms of titles, the major surprise of 1965 was the defeat of long-standing heavyweight kingpin Billy Joyce by youthful Billy Robinson, who had the home advantage at Belle Vue. Another upwardly mobile young northern heavyweight cemented his place at the top when Steve Viedor defeated Bruno Elrington in the final of the Royal Albert Hall Trophy Tournament. In Manchester, another meaningful and one-off knockout tournament for George de Relwyskow’s original gold and silver World Championship belt was won by Gwyn Davies, our “Shy Shooter of the North” once again the loser at Belle Vue.

In the lighter weights, Adrian Street was experimenting with hair dye for the first time whilst Bobby Barnes was tagging with another bottle blond, Gentlemen Jim Lewis. Later in the year Street and Barnes would appear for the very first time together as the Hells Angels. Barnes, incidentally, was in the midst of a feud with Jackie Pallo that spanned several years.

Two outstanding masked men continued to be denied television exposure and remained largely unconsidered by large geographical pockets of fans. One was in his final full year of masked campaigning, the other in his first. Read all about their momentous head-to-head when we turn the page next time to 1966.