One Year, Two viewpoints, as David Mantell Takes over

Wrestling Heritage welcomes memories, further information and corrections.

Wrestling Heritage concluded the Year of Wresting series with the year 1977, below …

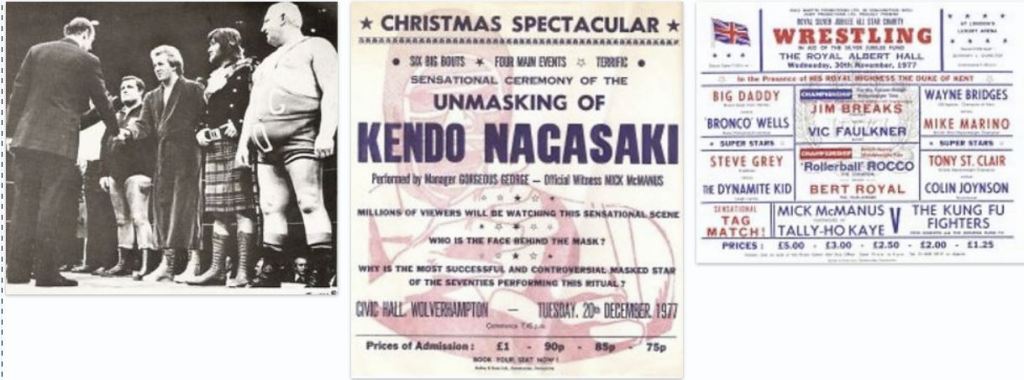

Ten years after HRH the Duke of Edinburgh’s last visit to a wrestling presentation, HRH the Duke of Kent followed in his footsteps to the November bill at the Royal Albert Hall, in this Silver Jubilee year of The Queen’s reign, a milepost we at Wrestling Heritage set as an approximate bookend of our interest.

If our occasional comments about management changes amongst the promoters leave you a little confused, just recall from our 1967 review that there had been 18 wrestlers billed on the Royal show. But only 4 Londoners and 4 Frenchmen wrestled in front of royalty. This after a 1963 Royal show where Northerners had been similarly side lined.

Now with Yorkshire’s Max Crabtree at the helm, the make up of the 1977 Royal card allowed space for only 5 southern wrestlers. On another royal note, isn’t it high time that, after a 14-year span of royal patronage and anecdotal evidence that TV wrestling was greatly appreciated by her Majesty the Queen, her Mother and her eldest Son, wrestling and wrestlers were honoured for their services?

British championships were still treated with respect in 1977, but all changes of champion continued to occur in rings from Wolverhampton northwards. In June, Bert Royal’s long run finally came to an end as he graciously relinquished his Heavy-Middleweight belt to Mark Rocco in Manchester.Tony St Clair, on the back of a much discussed 1976 televised defeat of McManus, progressed to heavyweight and started a new era as he dislodged Maesteg’s Gwyn Davies after the pseudo-Welshman’s on-off but mostly off eleven year reign.

At 15 stone 3lbs, Tony was the lightest ever British Heavyweight Champion, but the manner of this Belle Vue victory was scarcely satisfactory: Davies was disqualified due to an “accidental low blow”. What on earth prompted such a dismal route for the beginnings of a great reign?

St Clair would go on to be a reliable and appreciative heavyweight champion of the type sadly lacking, as bemoaned in our 1975 Year of Wrestling. He provided exciting entertainment with an ever-dwindling group of adversaries, who, though reduced in numbers, lacked nothing in guts and glamour. Bridges, Nagasaki, Roach, Jones – all would feature in spectacular action alongside the Mancunian.

But the dumbing down was hard to fathom just a couple of years later when Canadian John Quinn was allowed to challenge for the British title.

Manchester saw its third title change of 1977 when eighteen-year-old Dynamite Kid ended Jim Breaks’ six-year reign to claim the Lightweight Championship in May. But Breaks had mirrored Goldbelt Maxine’s 1971 manoeuvring, by claiming first of all the British Welterweight Championship from Vic Faulkner in March, and had enjoyed a similar period holding two British titles.

Kendo Nagasaki and Big Daddy continued their battles. The new management at Dale Martin Promotions had not studied and learnt how to make the most of a feud from their sixties predecessors who had used the Pallo versus McManus encounters sparingly and with deep national impact. The two heavyweights faced each other throughout the land, in increasingly gimmick-led matches, with ever more implausible outcomes.

Meanwhile at Croydon, Nagasaki entered into what George E. Gillette famously dubbed “A strange and unholy alliance” tagging with long-time enemy Steve Viedor, in defeating the pairing of Steve Logan (Wells replaced as he would be at the Royal Show in November) and Bruno Elrington. This was a bright spot in the creativity of the promoters, but an all too rare flash in the pan.

It is incredible as we look back on this final Heritage Year of Wrestling that we review in detail, to see that Wayne Bridges was still being billed as the heavyweight champion of Kent and featuring on opening bouts, such as at the Royal Albert Hall in April.

His development to a hard-hitting world champion followed fast in the next few years, following a Kensington victory over his largely undefeated mentor Mike Marino, but the push was way overdue in our opinion. We regret that we will not be able to analyse that progress in the detail it deserves ourselves within this Years of Wrestling series.

One bright development in 1977 was the emergence of Butcher Bond and Johnny Kincaid as the Caribbean Sunshine Boys. A provocative and hard-hitting pairing, the twosome took evil-doing to new heights and police escorts became the norm. See how they were elevated meteorically and justifiably to top-of-the-bill status at The Royal Albert Hall. After 11 months of action it was all deemed rather too risky and the tag team disbanded. Read more about this exciting period in Kincaid’s book, A Seat at Ringside.

A further comment would be that this clever development in increasingly multi-racial Britain carefully reflected changes in the ethnic build-up of society at large, and allowed fans to display more widely spread fears and prejudices within the confines of a wrestling hall. But this was just too much for limited promoters to handle skilfully. This controversy could have elevated wrestling once again to national consciousness level. Another 1977 trend was the arrival of punks on the streets and trains of Britain, but wrestling gave that particular novelty a wide berth. The punks could now take the tube all the way to Heathrow, with the extension of the Piccadilly line in 1977.

Johnny Kincaid was also the final opponent for Kendo Nagasaki at the end of the third quarter and it seemed the masked man may have fulfilled his outstanding contractual obligations, or had Kincaid seriously injured him in Cardiff?

The next time we saw Nagasaki was on a Christmas bill from Wolverhampton, ceremonial unmasking was arranged, complete with acolytes and mask-burning.

However, what seemed final at the time, proved, in true wrestling tradition, merely to be a fleeting episode in a career that would go on and on.

A few lucky southern fans had the good fortune to witness the return to the ring of veteran masked menace Doctor Death. Another plus point of 1977 was the introduction by Dale Martin Promotions of a tabloid sized glossy magazine “Wrestling Scene” which helped fans keep up to date with events nationwide 5 years after the demise of their beloved “The Wrestler”.

By the end of the year, Big Daddy had become a blue eye, a worrying development which paralleled the sharpest decline in British professional wrestling and was enough in itself to cause the two authors of this site, hardened fans over many years, to lose interest.

At the end of the year, a 1978 Wrestling Annual was published. The word “annual” had previously been reserved for The Beano and Dr Who, and this publication’s superficial and largely contentless banalities just served to concede what we had sought to turn a blind eye to for years, that matches were more about making a quick buck than long-term development of the sport, and that the target audience was kiddies.

It was a grim year for Hollywood with the deceased numbering Groucho Marx, Elvis Presley, Charlie Chaplin, Bing Crosby, Howard Hawks, Joan Crawford and Rochester.

Maybe they, like ourselves, couldn’t face the downturn in professional wrestling.

Once magnificently laid out and composed posters now proclaimed the cringeworthy coming of:

“Hilarious Catweazle – with his funny antics”

“The Mams and Dads Favourite ” (sic.)

“Popular Mick McMichael”

“Handsome Johnny South”

“Referee Bryan”

As a result, our memorabilia collections were put away, stored in attics, as our own young men’s antics occupied our lives, and later our wives occupied us!

We continued to peep in over the next ten years, but were seldom tempted to revive our once intense enthusiasm.

David Mantell took up the reigns , taking the story from 1977 onwards

A love dies, a love is born … As your previous correspondents were giving up on wrestling in favour of their families, a new generation of fan was sitting up and starting to make sense of the images on the family TV. I was three years old in 1977 and my working class paternal grandparents were dyed in the wool wrestling fans; indeed my grandma’s brother, my great uncle Jack, had been part of the London community of Catch wrestlers back in the Edwardian era, learning the crippling submissions in the gyms of the East End, a community by 1977 in its final phase and based around the office gym of Dale Martin at 313 Brixton Road.

Somewhere at my parents house, there is a projector slide of two cousins of mine grappling in the back garden of my grandparents’ home. So it was that the hereditary love of wrestling was being passed down to this young whelk, high chair placed in front of the lounge television.

Ironically it was a good year for a three year old to be getting into wrestling as this was the year when Big Daddy completed his transformation from the heel/tweener “Blond Bombshell” to the purely blue-eyed People’s Champion (or Mams And Dads Favourite. Not that my mam or dad – doctors the both of ’em – cared much for the wrestling. It definitely skipped a generation there.)

The feud pitting Daddy and Giant Haystacks against Kendo Nagasaki had in many respects been the prototype for the two erstwhile TV All Stars tag partners’ many feuds with each other, or Daddy’s own later feud with Mighty John Quinn. Kendo’s controversial cuts win over Haystacks from a St George’s Hall Bradford TV bill was one of the last great battles of this feud – and one of the last times for a very long while that an audience gave Haystacks any sympathy. Certainly until it all kicked off again between Kendo and Stax in the early 90s.

Results from the earlier part of the year indicate that the two big men were still teaming up to give poor helpless blue eyes a pasting and a sandwiching. But this was something of an era for throwing together tag partnerships between people who were either sworn enemies or no longer friends. In the past year Kendo had at least once walked out on a tag team with Daddy mid-match while attempts to reunite the Dennisons tag team around this time ended in tears as, thanks to Dynamite Kid, Strongman Alan was no longer the natural buddy of Cyanide Sid but a better holier and frankly more sanctimounious man (We’ll get back to him around 1979/1980).

But anyway, if what Daddy himself told me in Croydon in the summer of 1990 is to be believed, 1977 is the year when the big man team finally broke asunder when “‘E ‘it me over the ‘ead with a chair! An’ that was the end of that!”

Regardless of what may have been shown live to one or more audiences around the country, as far as TV was concerned, it all kicked off in December that year. Not unlike the Daddy/Kendo feud two years earlier, it all began with a four man knockout tournament. Unlike that feud, this time Daddy and Haystacks were in opposite semifinals and both made it to the final. Fifteen seconds after the start of Round 1 with not a finger laid by either man, Stax walked out of the ring and an urban legend started – Stax, it seemed, was frightened of his former mentor, the one man who could conceivably beat him. The fact that Stax had already shown he could squash Daddy way back in April ’76, when Steve and Tibor posted him into a cornered trapped Daddy leaving the blond Yorkshire then-heel quite flattened, was immaterial. Daddy wanted a piece of Haystacks and Stax seemed strangely reluctant to give it to him. And that was how their feud was built to run. After one TV singles match (conveniently forgotten by the time 1981 rolled around) ended in a double DQ, the two big men next went to war in a tag match partnered by Tony StClair (another participant in the Sept 77 heavyweight TV tournament) and Baron Jack Donovan respectively.

This was the second ever of the formula Big Daddy Tag Matches to be shown on TV. A pilot TV match had been shown back in July at the time of the Jubilee, with Daddy and Bobby Ryan beating Man Mountain Mike Dean and Filthy Phil Pearson. A somewhat nauseous-looking sequin caped and hatted Daddy, surrounded by sequin-hatted little kids had been photographed at the taping with the result printed in TV Times in glorious colour for the World Of Sport details panel. Out in the halls, one of Daddy’s other tag partners had been Dynamite Kid when he wasn’t busy winning the British and European Lightweight title and then getting the double crown again at Welterweight (in January 1978), or else playing the 123 Kid to Alan Dennison’s Razor Ramon.

In fact the Daddy tag formula really dates back to 1973 when Kendo and George would face Battling Guardsman Shirley and kid brother Brian. But by the Wolves Christmas TV taping, the format was fully in place for Daddy plus blue-eye to face Stax plus heel and features of many a main event tag match for Joint Ring Wrestling Stars up to 1993 were debuted before the TV public in that match.

Another important matchup to come from that bout was Haystacks against St Clair. Tony had gained a rare win over the mighty Mick McManus and then beaten Gwyn Davies for the British Heavyweight title that year on a disqualification (as was to become a bit of a habit for StClair) and back in the late spring/early summer had – possibly – given Daddy one of his last chances to heel it up when Shirley somehow got himself DQ’d during a title show against the son of the legendary Francis StClair Gregory. St Clair would go on to be a regular in the Daddy tag partner role during the first flush of the feud with Stax. In time it would cross over to the scene of StClair’s title.

Meanwhile another potential challenger for StClair, the TV All Stars’ former nemesis Kendo Nagasaki was off making a bit of history of his own at the Wolverhampton TV taping, with his unmasking ceremony “never before performed voluntarily in this country” – the “voluntarily” a reference to the unmasking inflicted by Daddy in ’75 not to mention the near unmasking by Billy Howes in 1971, the “In this country” perhaps a hint that Kendo had lost his mask in Stampede the night of his losing the North American title back to Geoff Portz back in late ’73. Regardless, this was no slapstick mask-pulling, no sad compelled unhooding after a first loss in however many years but as George put it, a “fulfillment” – an “unveiling”.

A year earlier, interviewed by TVTimes, “Yogensha” (as Nagasaki likes his out of character self to be referred) had indicated that he would unmask and be Nagasaki without a hood when he felt ready and mature enough to do so. Now twelve months on, in a bizarre religious ceremony, two “acolytes” with shaved and pony-tailed hairstyles just like what we had briefly glimpsed of Nagasaki in December 1975, prostrated themselves in front of the kneeling Kendo as George, in blue and gold priestly robes, peeled off the headgear and burned it on the fire. So astonished were the Wolverhapton audience that Kendo had not found a way out of the ceremony but been true to his word, that they all cheered the unmasked man – having a big impact on storylines for him for the coming year.

Further down the bill, before Dynamite Kid got his mitts on the British Welterweight title, it had been the subject of an almighty feud between Vic Faulkner and Jim Breaks which saw no less than four TV matches. The normally clean and classy Faulkner had got himself disqualified to lose the belt to Breaks. Vic then atoned for his sins and regained the belt before losing it back to Breaks at the Royal Albert Hall in the special Silver Jubilee show. Another rising star and fellow future globetrotter like Dynamite, Rollerball Mark Rocco, formerly of the Rockets tag team but now a promising violent heel, also got a big break this year when he won Eric Taylor’s old belt, the British Heavy-Middleweight title, beating Faulkner’s brother Bert Royal. Meanwhile over in Brian Dixon’s Wrestling Enterprises (the future All Star) former TV and future American star Adrian Street was riding high as World Middleweight Champion, since winning the title the year before after the previous Spain-based version died along with its parent company the CIC back in 1975. At Street’s defences in the Liverpool Stadium, a young Robert Brooks looked on in awe and saw what he wanted to be in life.

No discussion of 1977 would be complete without mention of one of the most controversial gimmicks of the era, Dave Soulman Bond and Johnny Kincaid’s infamous Caribbean Sunshine boys. In October 1977 midway through a tag match in Croydon, Bond and Kincaid suddenly turned heel on clean opponents Pete Roberts and Eddie “Kung Fu” Hammill, roughing up their opponents until they got disqualified. Also roughed up was a spectator who threw water at Bond and lived to regret it. The newly heel tag team adopted a provocative and blaxploitative gimmick with their swaggering demeanour and flamboyant high-five gestures Not only did the gimmick draw racial heat from the audiences, it also attracted far dimmer parties such as the National Front who threatened to turn up at wrestling shows to harass the team. Max Crabtree eventually put the kibosh on the team although elements of the team were continued by Bond, especially in his matches against St Clair. In America, a few African American wrestlers had been heels up to this point, but they were generally big towering individuals such as Ernie Ladd and Reginald Sweet Daddy Siki. The Sunshine Boys’ problem was that they were provocative but small enough to look a manageable target for violence from bigoted punters.

With Daddy and Stax now warring via the tag matches and fans cheering an unhooded Kendo, the stage was set for 1978 …

Suffolk Punch 24 added:

Jim Breaks defeats Vic Faulkner by disqualification to win the British Welterweight Championship. Vic wins it back. Jim then wins it again at The Silver Jubilee show at The Royal Albert Hall.

Ohtani’s Jacket added:

I don’t think you can mention St. Clair’s elevation to the British Heavyweight Championship without noting his upset win over McManus in March that year.

One of the big stories that year was the Caribbean Sunshine Boys not only for their one televised tag but Bond’s singles matches with Tony St. Clair

The Faulkner/Breaks feud was a big enough deal that it produced four singles matches on TV

Tony added:

Vic Faulkner losing the Welterweight belt to Jim Breaks was the significant feud on TV and at the RAH in 1977

Mike Marino’s parade of the new faces on Dale Martin’s shows was another significant change as was his booking and forming of various tag teams