By Ruslan Pashayev

Clog Fighting Tales

Part 2: A Clog Fight In Rishton

A few years ago I was lucky to obtain an audio record of an interview of Daniel Tattersall who was born in 1917 at Church, Lancs. That interview was made in 1994, when he was 77 years old. I immediately shared the audio record of this interview with my dear friend Hack and it he helped me to better understand the interview which was spoken in a dialect native to Lancashire’s residents. Hack also helped me with the genealogy of the Tattersall family to understand the time frame of the described events from the past. The Tattersall’s interview was crucial in my studies of this subject and helped me to finally explain the nature of the Lancashire clog fighting game thus putting an end to all the misinformation which has accumulated for decades.

In his interview Daniel Tattersall gives all the necessary information about the rules of Lancashire Clog Fighting as it was practiced by his father and his peers the working class men of Rishton, Lancs. Daniel’s father, Arthur Tattersall of Rishton, Lancs, (born 1884 – died 1959), was a collier by trade, a son of John Tattersall, who was a weaver.

According to Daniel Tattersall clog fighting was a way of settling neighbourly arguments. This pastime did not disadvantage the smaller man, unlike other forms of fighting. Matches took place on any spare ground or “back end,” which means behind the houses. Betting was common. Daniel Tattersall had never witnessed a match, though he saw dents and scars on his father’s legs, and his knowledge of the game was based on what his father, who himself was a clog fighter, told him about it. Daniel Tattersall died in 1997 at Blackburn. Below I am giving a transcript of the parts of that interview where Mr. Tattersall fully and completely explained clog fighting.

“At Rishton, on Spring Street, and they told me when I was a young lad, that my father was involved in a clog-fight on Saturday evening. He was going home and had his shoes on and this man challenged him to a fight, a clog-fight, and a clog-fight in those days meant that if two people had a dispute they would settle it by a clog-fight. So he said wait there and I will go get my clogs on. And he came back.

What you do is you place your arms on your opponent’s shoulders like that, and when a word is “Go!” between you, you kick at one another, but you do not take your arms off your opponent, you just kick. That particular fight lasted about three minutes. In which case his opponent went down and that was it. Once he went down on the floor he was a beaten man. Well, they had to keep hold, didn’t matter what they did, they could do any turning they wanted as long as they didn’t release their hold, once they did that they had lost, whether they were beaten to the ground or not. If they loosen the hold they lost. It lasted about three minutes and he got one good kick and that was enough to put him on the ground. And that was the end of that, and the dispute was settled.

I asked him what the grudge was. And the grudge was apparently they have been to the club and got into an argument about the price of a pint and when they couldn’t settle it by such means he decided that they will settle it by clog-fighting. And my father obliged him and won. He didn’t say anything what they had to wear, only that they have to have clogs on. Clogs in those days were with irons on. I can believe that my father had a few scars on his legs, he got them when was learning how to clog-fight. It was a common thing to settle arguments that was one way of settling arguments which mainly developed in those clubs they went to and it would nearly quarrel many a time and they would take one another to task get your clogs on and we have a “Go!”

I never witnessed a clog-fight. All I can talk about is the facts that my father talked about. He was never permanently injured by anyone. He had a few dents on his legs which I saw. At the back end (they fought), anywhere, on the spare ground. That was a common thing, betting. It was a working men’s’ sport, that is what they called it.”

Another similar audio record, an interview of Harold Shorrocks (born in 1917 at Church, Lancs) also sheds some light on this matter. His memories are also based on what his father, who died in 1970, told him. Harold Shorrocks shared that his grandfather was a famous clog-fighting champion of Darwen, Lancs, and mentioned that they used to have similar “puncing” matches in Wigan, Lancs too. He said that clog fighters would get injured legs and that a smaller, weaker man could get an advantage in that kind of fighting.

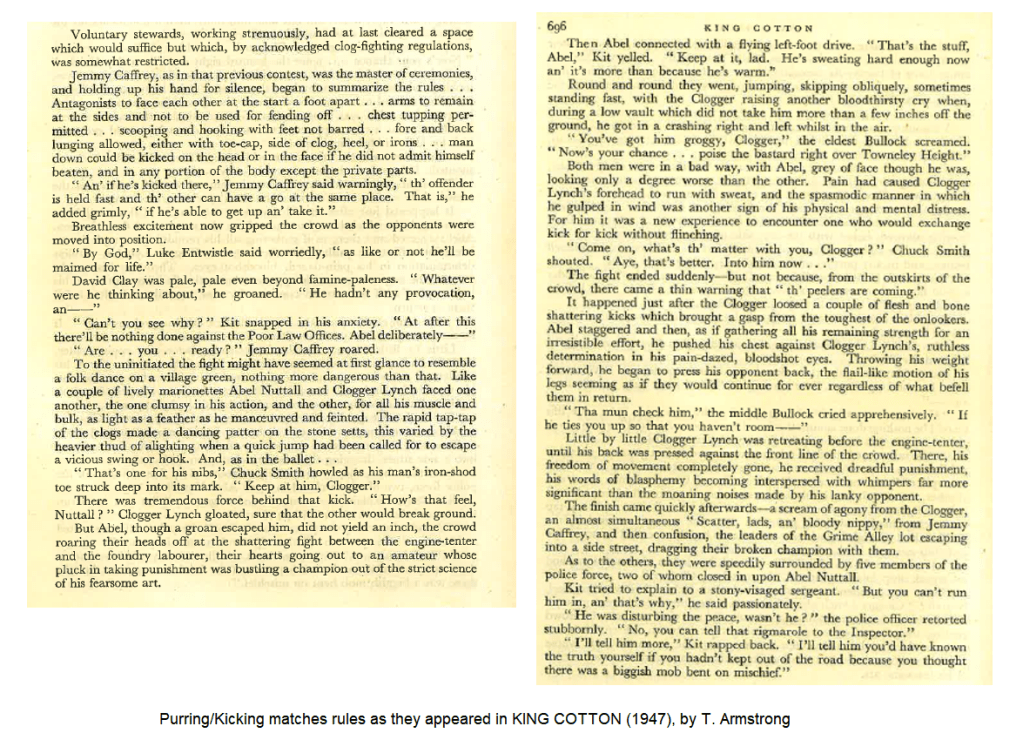

This vivid description of the Lancashire’s up and down fighting comes from the contemporary, nineteenth century, newspaper. Apparently the prelude to the actual fighting was nothing but an old English fair upright wrestle in which kicking shins and tripping feet was the major feature.

“We transfer to our column from a Liverpool contemporary a graphic description of “scientific” brutality as practiced in Lancashire. The degrading pastime of “purring,” it appears, is peculiar to that county, and the writer, who has evidently been an eye-witness of what he describes, gives a fearful picture of human ferocity among the South Lancashire colliers and ironworkers in the pursuit of this brutal and barbarous indulgence. For the benefit of the uninitiated, it may be useful to mention the leading features of what is termed “the style “down i’ Lancashire,” in which her stalwart “lads” are so fond of showing their prowess, with more than the courage and all the savagery of the wild beasts of the jungle. “Purring is the local synonym for kicking, and a fellow who can “purr” in “style” is hailed by his contemporaries as a wonderfully clever lad dexterous in the use of the foot, armed either with hob-nailed shoes or iron-plated clogs. “Scientific purring” we are told, is only a playful term for something very dreadful, it means neither more nor less than deliberately kicking a man’s eyes out, or causing his brains to protrude through the skull, or the breaking of his ribs, and, may be, the breaking of his neck. The “play” is managed in this way: The players strip naked to the waist, then face each other, try to get a grip of each other, as if in the act of wrestling, and twist their legs together so that one may fall; and should the uppermost man be at liberty, and have the under man at his mercy, the partisans of the former excitedly shout, “Na, tha hes him; go into “him; purr his yed; good lad; tha’s warming…”

Some other accounts provide evidences that often time clog fighting contests were conducted in rounds, and every time one of the two fell to the ground, the round was over. Just like any upright wrestling games those fights were decided on actual physical falls, and they would fight as many rounds they needed until one is no longer able to get up and continue the fight, as well as that it was allowed to use legs and feet for throwing your adversary down (not only kicking but also tripping was OK), and that it had to be only fair kicking below the knee, using strength of your grip and of the arms, pushing, pulling, hauling, swaying, and etc to unbalance your opponent was all OK (any “turning” was allowed), and the hold had to be maintained during the struggle just like it is in collar-and-elbow wrestling, you couldn’t let go of your opponent until you felled him.

Yes, as mentioned above, sometimes the clog fighting contests were played in rounds; each felling of a man ended the round, but not the match. Generally the match would consist of a certain number of such rounds and would continue until one of the two was no longer able to endure the pain and cried “enough!”

‘Yi! aw remember that, Malachi,’ said the old woman, proudly recalling the days of her youthful prowess; ‘there were no man ‘at ever insulted me twice.’ ‘When aw see th’ tackler put his arm raand Betty, I were through th’ dur and down th’ alley wi’ a hop, skip and jump, and hed him on th’ floor before yo’ could caant twice two. We rowl’d o’er together, for he were a bigger mon nor me, an’ I geet my yed jowled agen th’ frame o’ th’ loom. But I were no white-plucked un, an’ aw made for him as if aw meant it. He were one too mony, however, for he up wi’ his screw-key and laid mi yed open, an’ I’ve carried this mark ever sin’.’ And the old man pointed to a scar, long since healed, in his forehead. ‘Then they poo’d us apart, an’ said we mutn’t feight among th’ machinery, so we geet up an’ agreed to feight it aat i’ th’ Far Holme meadow that neet, an’ we did. We fought for over hawve an haar, summat like fifteen raands, punsin’ and o’ (kicking with clogs). As aw told yo’, he were th’ bigger mon; bud then aw hed a bit o’ science o’ mi side, an’ I were feytin’ for th’ lass aw luved, an’ when he come up for th’ fifteenth time, I let drive atween his een, and he never seed dayleet for a fortnit.’ ‘An’ thaa were some stiff when it were all o’er, Malachi,’ said Betty. ‘Yo’re reet, lass! Aw limped for more nor a week, but aw geet thee, an’ aw meant it, if aw’d had to feight fifteen raands more–‘ ‘So, like the knights of olden time, Malachi, you fought for your fair lady and won her.’

Lancashire Idylls (1898), by Marshall Mather.

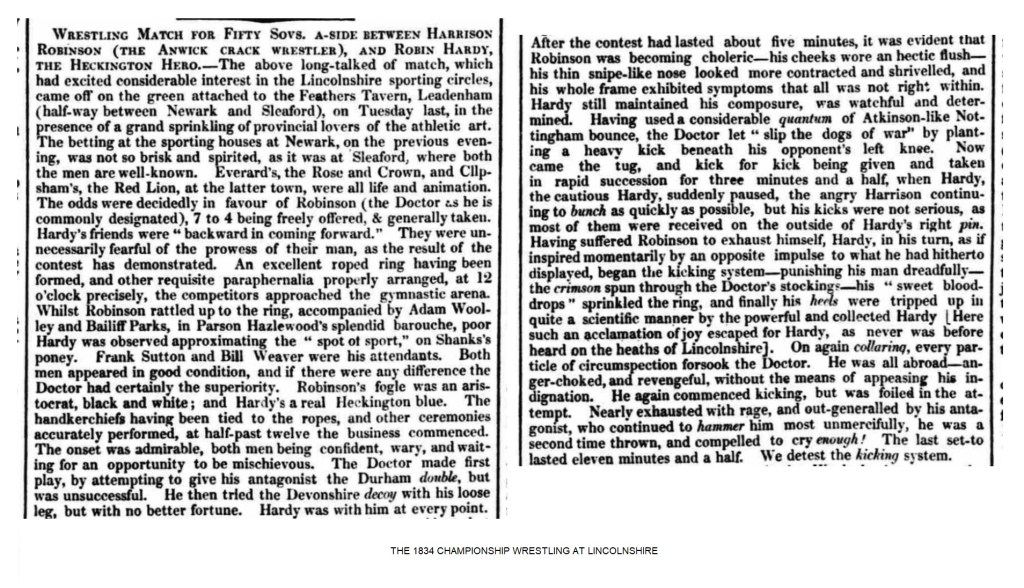

This “rounds” system had a very strong resemblance with the collar and elbow wrestling matches after the Lincolnshire fashion (the deadliest “kicking form” of traditional English wrestling) in which they only recognized the fair falls on the backs and didn’t count the number of half-falls (read rounds). Thus said the combatants would collar each other and desperately kick shins for many, many “rounds” (go-downs) until finally the fair back was given, after one of the two was no longer able to stand and simply was pushed backwards, tripped or back-heeled. Interestingly, in 1834, the Lincolnshire championship wrestling match ended differently, one of the two simply quit the bout. Yes, Lincolnshire wrestling was in fact very similar to the old Lancashire clog fighting. And this fact makes me think that originally the clog fight was a form of Lincolnshire wrestling which over the time degraded and transformed into “something else”. And not only that, their wrestling or better say kicking fashion has evolved far and beyond, the Lankishir wrosler developed a certain habit that of finishing his felled opponent kicking him into senselessness thus ending the match.

“Would you kick a man when he is down?” cried an indignant bystander to a Lancashire wrestler, and the reply was, “It is precisely because he is down that I kick him.”

“MONDAY, FEBRUARY 2.-This may be deemed a day of mishaps, only one event being brought to a satisfactory conclusion, although there were four on the tapis, viz., a wrestling match, a coursing match, and two foot-races. The novelty of a fair day, although windy, made the grounds wear their wonted animated appearance, and the bill of fare promised lots of amusement; but the preamble of the wrestlers, one kicking the other, after a throw each, put an end to that affair. This was succeeded by a rabbit coursing match, with no better success.” (Wrestling at Belle Vue, 1850s).

Notably, the earliest known to me 19c newspaper reference to a professional wrestler from Lancashire is that from the 1820, and it speaks of a Lancastrian being matched with an Irishman (who definitely was a collar-wrestler, so to speak a proficient a kick-master) in London. On the first day the match was not decided, and had to be resolved. On the next day, the outcome of that historical bout remained unknown. The 1760s newspapers speak of a wrestling match between a certain Mancunian and a man from Cheshire which also occurred in London, the former won 6 falls (I am assuming rounds, the so-called 2 joynt-falls) to 4 in 42 mins, no doubts it was another deadliest kicking exhibition.

20157