Romany Riley v John Kowalski; Romany Riley v Len Hurst; Romany Riley v Clive Myers

Wrestling Heritage welcomes memories, further information and corrections.

Why did Romany Riley never become a big name bill topper in professional wrestling?

Why the question?

The compelling overall assessment is of a hard hitting athletic heavyweight who had the versatilty to assume various roles, but always to deliver with a very believable edge.

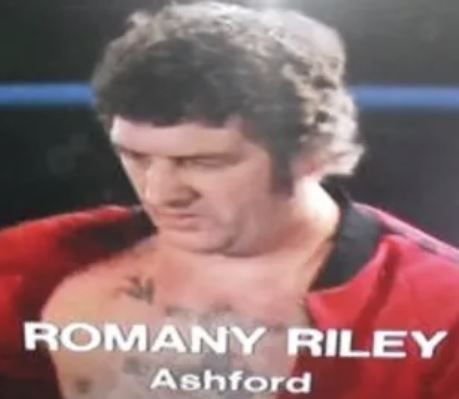

Coming to this verdict is one of the most enjoyable parts of writing these reviews of the televised bouts, for we remember with great clarity the slow and hesitant heavyweight of the early seventies, attired in ill-fitting trunks that crawled up his girth, and certainly never featured in small screen action. In fact, the most notable aspect of his presence on a bill was the racket that was made by his seemingly endless family members who accompanied him to the halls.

Everybody has to learn, and wow, what a metamorphosis to behold in these bouts. A few more wrestlers like the leotarded Basil and our faith in eighties wrestling could almost have been restored!

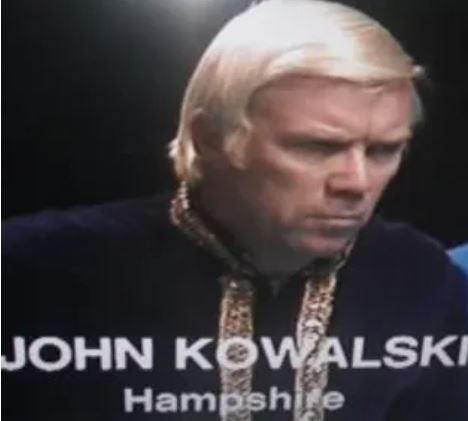

In opposing the imposing but unadventurous John Kowalski, the Man of Kent is seen as many will remember him: a quiet under-achieving undercarder, clean wrestling but never ever seen to smile. This was one of his very early tv appearances and the mutton chop sideburns were still there. Oh, of course we can look at the result, an entirely predictable single fall victory for the Hampshire farmer.

But look at the technique through the bout, watch those rolls and the forward planning – Riley was so far ahead of Kowalski that he left the more experienced pro flat footed and foundering. In the end he carried the bigger man to the end result. The winning pin-fall was, incidentally, mischievously and mysteriously zoomed in on to reveal a Riley shoulder high high off the canvas as referee Mancelli hurriedly counted to three. Kent Walton seemed not to enjoy the fayre, but Kentish Man Charlie Fisher seemed far more appreciative as he called for applause.

Facing Len Hurst must have been quite a challenge. Regardless of varying hair and trunk styles and initial leaps suggesting a spectacular performance to come, Hurst made a career of delivering the same performance night after night. All those U.S. tours and bulking up did nothing to develop the style of yet another unsmiling product of 313 Brixton Road, and he remained the very junior Honey Boy we remember from 1968.

Good match-making and thoughtful role development from Romany Riley made this encounter a real treat. Note the words role development. So many wrestlers had their attitudes established before they entered the ring, only to embark upon meaningless unprovoked rule-breaking. Not Romany Riley. He started clean, lost a fall in the first round, and that provided the impetus for a mini heel-turn. Nothing exaggerated, just understandable frustration at potentially being outwrestled. One other who springs to mind for this thoughtful developmental style is Bruno Elrington, but they were few and far between.

True, that opening fall was rather sloppily executed but it was more than made up for by the cross-ring arm roll and joint exit over the top rope that led to the double knockout. This finish is the most commonly used route to a dko but is rarely executed in a smooth, single flowing action to make it look believable rather than forced. Here they hooked up and rolled out as one in flowing unison. The landing looked hard. It was surprising to see Joe D’Orazio almost embarrassed into not reaching the ten as both wrestlers had felt they needed to be seen to be getting back in fairly quickly.

In between, we saw Riley marvellously selling drop-kicks galore, surviving an aeroplane spin in which he unusually maintained a wristhold, taking a believably heavy head posting and gradually turning to foul play. It was noticeable how quick the audience was to express its dislike of the man billed from the Romney Marshes, which Kent Walton decided needed to be deglamourised from a plausible gipsy caravan location to the rather mundane Ashford. Hurst played his role well, but unmemorably.

Perhaps we witness the very best of the mature Romany Riley in an explosive match as he had an advantage of four stones over “Iron Fist” Clive Myers. While Bobby Palmer introduced this heavyweight bout (sic.) with all the fireworks for colourful Clive, as usual the most exciting description available for Baz was that he was from very uncolourful Staplehurst. Myers was a very tricky opponent for most pros in various respects, but Riley proved the perfect foil. And Riley’s own performance shows a whole variety of technique and strategy with very little repetition, marking him as one of the game’s great thinkers.

Once again, with his trademark clean start, we were able to see the heavyweight displaying his speed and agility but then, gradually and according to plot, being outwitted by the lighter man. By the time he has conceded the first fall in round two his patience snaps and he delivers a blatantly illegal mid-round posting. A delightful Waltonism of questionable taste attributed this aberration to the fact Romany had recently lost his mother.

So from the third onwards we see Riley the out-and-out villain – and what a great job he made of it. One of our very first articles considered the unsung hero that was Tony Walsh, a villain we have since acknowledged as a very skilful grappler. In Romany Riley we have another unsung hero. Little acknowledged for undoubted technical expertise, and equally unheralded as a rogue of the very nastiest type. Once again the crowd were only too willing to turn on him, here understandably, and we can only surmise this could be due to his appearance as one of those tattooed unlicensed boxers that abounded in the Garden of England at that time.

The baddie gained an equaliser. Then he selflessly put up with Myers unbelievably showing his invincibility, a spot that blighted most of Iron Fist’s bouts, before making his own glorious exit to being knocked out by virtue of a nasty looking bump on the ring apron.

After the wrestling bout Bobby Palmer redeemed himself by very believably setting up an impromptu arm wrestling challenge, issued even more believably by Romany Riley. We have all witnessed some pitiful exhibitions of the elbow game, Big Daddy versus the Mississippi Mauler striking a particularly raw nerve, but this was well executed and the champion dutifully strung it out before claiming an inevitable victory.

Whilst the plaudits were for Myers, it was Bad Loser Baz who stole the show for us, predictably overturning the table but then rather satisfyingly having a real go at the Magyar referee, before departing, all gob and spit, taking pot-shots at angry fans on his way.

Such is Romany Riley’s lack of stature in the paid ranks that it would be and invariably is all too easy to overlook his contributions. But pause and analyse awhile and you may well discover a hidden gem that has been before your very eyes all these years.