Wrestling Heritage welcomes memories, further information and corrections

The use of the speciality move in wrestling created an automatic high point in each bout. Many but by no means all wrestlers had a speciality move attributed to them almost as inextricably as their home town. In many of these cases the speciality was in actual fact quite benign but the whole business was strictly organised so that every speciality was respected fully. The respect was shown by allowing clear openings for the speciality well into the bout, and displaying appropriate suffering when on the receiving end.

Where to begin? If we were to ask a passing fan about a speciality, perhaps the most likely reply would be The King of the Head Butts, Johnny Kwango. Kwango was a popular colleague and down the years we can see every opponent without exception selling the move exaggeratedly.

Not just in reacting to being butted, but in steering clear of the famous bonce often from before the opening bell, antics which invited maximum audience participation in traditional pantomime style. There is no doubting that, in the case of the Kwango head butt, the industry united in perfect harmony to convey the message or create the illusion that his head was very very hard indeed.

How dare we criticise something as deep-rooted at the epicentre of professional wrestling as Kwango’s head butt? A personal view is that the move was as valid as Kwango being the official Champion of West Africa, from Lagos, as we were told. It didn’t even look real as the opponent’s head was covered by a hand. The opponent was required to bounce from the bonce and none bounced higher or further than Bobby Barnes – he deserves 50% of the credit. The funny thing is that Kwango had another scarcely reported speciality, equally untechnical and equally sold by his loving foes – the jaw hold. And that’s all it was.

Such was the success of the head butt that several other black wrestlers hopped on the bandwagon almost as if to perpetuate a myth that their heads were harder: Masambula dabbled, Moser too, even Honey Boy Zimba. It’s a shame in Zimba’s case because he had so many truly spectacular special manoeuvres of his own, from the plank to the flying head butt, but even these gems paled into the shade alongside his occasional imitation of a Kwango butt.

So at last we touch upon really special specialities, that perhaps have their roots in the famed rolling body scissors expert of the thirties and forties, Charlie Purvis who wrestled as the constricting Anaconda. In the 1955 Carol Reed melodrama, “A Kid for Two Farthings”, which has professional wrestling as a central theme and plenty of good action and familiar wrestling faces, Primo Carnera’s character has the ring-name Python (off-shoot of Anaconda). In the main bout of the film, Python crushes the hero by means of …. the rolling body scissors. Look down the credit list of the film and, surprise surprise, the wrestler who played the champ was one Harry Purvis.

Purvis was followed in the early sixties by Doctor Timmy Geogheghan, the sleeper hold practitioner, who would invite members of the public into the ring before his bouts for a demonstration. That flying head butt of Honey Boy’s seemed to become the domain of heavyweight champions such as Dazzler Joe Cornelius, and Ray Steele. However, when delivered by Albert Wall to end a bout in quite spectacular flight, no fan ever complained. He really ran risks in its delivery.

As Knowers after the event, and it has only taken us forty years to work things out, aren’t we so very clever, it is interesting to identify specialities which really seemed performable by only a few or an individual and which seriously looked to have a painful impact. Kendo Nagasaki’s kamikaze roll which appeared after his return from North America, was a sight to behold and probably accounts in no small measure for his popularity. As in many cases, credit also goes to his opponents who took this very dangerous looking bump. Presumably many refused.

Jim Breaks really milked the twists and turns of wrist and elbows that went into the execution of his Breaks Specials. The result usually looked very dangerous and painful and nobody doubted the victim’s sense in submitting. Again, this drawn out struggle, at the very core of professional wrestling, invited maximum audience participation and suspense, both literally and figuratively!

Breaks had the magnanimity to allow his own speciality to be reversed and used against himself, as by Mike Bennett, and this self-deprecating modesty is what we love about a few of our favourites.

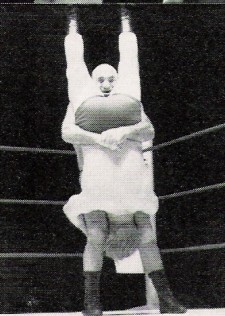

In this category we also comfortably include the short arm scissors of Geoff Portz; the sapping backbreaker of Julien Morice; the rolling arm-scissors of Kiwi Kingston; and the not dissimilar rolling arm lock of Mr X. Not to mention another suspension hold practitioner, Gwyn Davies.

Other speciality manoeuvres just left us wondering.

Zoltan Boscik’s three-in-one certainly looked uncomfortable, as much for himself as his victim. Quite how much it hurt or was a mere balancing act is open to debate. Judo Al Marquette’s hand tie is another unfathomable – just how willing did the opponent need to be? George Kidd made a living out of rolling up into a ball and even handed the baton of the same move to Johnny Saint. Here we are more in the realms of gimmick than technique, a surprising anomaly considering these lightweights were supposedly the masters of a thousand holds.

Then there were specialities that left us in little doubt. The hangman’s hold favoured by Bruno Elrington and Gargantua can claim a marvellous name, but was, in truth, harmless looking and only ever worked at all thanks to Tibor or Viedor having their knees high and wincing effectively.

The bearhug, as applied by John Elijah and Mal Kirk or even, heaven forbid, Crusher Verdu, could have hurt, but they all clearly made little attempt to tighten their grip. The booby prize must, however, go to the tomahawk chop of Billy Two Rivers in which he scarcely made contact at all but paying audiences had to be disappointingly short-changed with a knockout.

Set pieces, in some cases, were not even holds, just theatrical vignettes that the audience awaited and everybody felt comfortable seeing. Think of Johnny Czeslaw hooking his leg under the bottom rope or Vic Faulkner getting his opponent to look up at the lights; think of Masambula upside down on the corner post inviting a villain to foul him; sixties Nagasaki with his cold steel coming down to within a nostril of slicing his opponent in half – there was truth in this as many a foe stepped away but the likes of Steve Viedor heroically, genuinely, unflinchingly and trustingly stood his ground; Big Bruno banging the canvas when wrestling clean in the early seventies against a villain to signify the end was nigh. Thus some specialities didn’t even involve any contact.

There were locks and chops, too. The Indian Death Lock as expounded by Sean Regan seemed genuinely inescapable. South African Olympian Maurice Letchford had introduced the hold to the UK before the second world war. Andy Robin had his own power lock but his arrogance made everything about his ring performance questionable.

Less superficial than the Tomahawk Chop was Nagasaki’s Atomic Chop, but not by much. The Szakacs brothers favoured a backhanded slap to the chest which was strong on dolby surround and must have hurt, yes indeed, we saw the victims’ red chests.

Equally cracking were the forearm smash and forearm jab as famously executed by Steve Logan, Joe Murphy and Mick McManus, though you wouldn’t have wanted to be on the receiving end of one from Bruno or Billy Robinson. As fans, we rejoiced in the in-depth knowledge of being able to distinguish the jab from the smash. In truth, one was linked with one name and vice versa. Logan rather devalued the whole concept of the speciality by overuse of the smash in many of his bouts – in the regrettable absence of other technique.

Beyond that, there were suspension type holds. The surfboard was so often a manoeuvre attempted by the likes of Ken Joyce but seldom completed. Kidd seemed to manage with more success, at least on Adrian Street. So did Bert Royal. Aerial manoeuvres never failed to captivate and Ian Gilmour’s flying double leg nelson was a treat to behold.

The flying tackle as performed by Viedor and Tibor, the pair once again named interchangeably, needed to be sold well by the recipient and Bruno and Gwyn Davies could string it out over endless seconds – would they or would they not topple over? Bernard Murray had a fluent Victory Roll. We enjoyed the risk and revered Les Kellett for being the only one to attempt his very dangerous rope roll to return with a head butt. His timing was poor in later years – but that just added to the risk to himself.

While we are on the ropes, an honourable mention to referee Joe D’Orazio for his own more sparing use of them. When the occasion arose he would fly headlong between the top two, pivot around the centre one, and dive down to a vertical position, his legs upwards, to secure a vantage point from which to see and count off usually a winning score. A review in Armchair Corner is named in honour of this refereeing speciality. There was no greater protector of the integrity of the game than stuntman Joe, and he struck the right frequency of use of this rather risky dive when he must have been tempted to apply it with more regularity.

The wrestler’s bridge was always vaguely impressive whether from Al Hayes or Alan Sargeant or many others, most particularly when used to secure a pin-fall in some way. Berts Royal and Mychel could really get height from their monkey climbs, and Mike Powers claimed this as his speciality, too.

Mike Marino had his own small package body cradle, and he also used an unusual leg stretch submission. Drop-kick Johnny Peters was not alone and fifties Jumping Jim Hussey gave a demonstration of how he could jump from and land back down on a pocket handkerchief. Jumping Jim Moser took the title when sixties Hussey went for a more down to earth style.

It should be noted that this move at the very centre of professional wrestling, and with no amateur roots whatsoever, was introduced by Jumping Joe Savoldi and from him followed not only the drop-kick but the very epithet for its specialist exponents. Unheralded in this field but, from a very personal angle, the absolute master of the extremely dangerous running drop-kick, was Romany Riley.

Romany Riley and Steve Viedor are linked, incidentally, in that Kent Walton persistently underlines that both claim no speciality but a desire to master all the holds.

Don’t forget the kicks. Caswell Martin’s La Savatte mule-kick needed to have a clear impact to be believable and only worked half the time. How on earth Peter Rann got away with his so-called Karate kick, the lord only knows, it was most unsatisfactory and nothing really. The wrestling press of the time had us believe it was a martial arts kick – sheer baloney!

Masambula let himself down similarly with a silly grip to the back of the knee.he colourful names of these holds do much to add to their status. Kent Walton famously named the “semi-Jap-strangle” but the perfectly adequate self-stranglehold had been available for some time.

This semi-self-strangle was a favourite of Les Kellett’s as he wound up Arras or Yearsley or Graham centre ring only to swing round with a kick or an elbow to the head. Low on impact but high on theatrics.

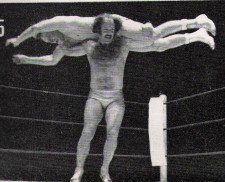

The best thing that can be said of a special hold is that it automatically led to a score, and Ricki Starr’s aeroplane spin was fast and incredible in that he would often hoist even superheavyweights aloft. Jackie Pallo didn’t shirk from the dangers of a piledriver or his own patented sit-on backbreaker and arm stretch, Bert Royal the victim. Quasimodo used a pendulum piledrive.

Associated with special holds are what we have termed “anti-specialities” where the way the victim sells a particular move is especially noteworthy or individual. Back in the sixties Nagasaki was once again the innovator, taking a posting and ending up sprawled across the corner over the two top ropes. Logan manfully stuck out his chest to give his more athletic opponents an easy drop-kick target.

Mark Rocco took these anti-specialities to a new level at the tail-end of the period we describe, turning a somersault into the cornerpost. That man Nagasaki gets yet another mention for how he let his mask get pulled up to his nose in every bout, and Wild Ian Campbell would always get wrapped up in the top ropes and look lost and bewildered.

But perhaps the greatest of all in this category were the cauliflowered ears of Mick McManus: “Not the ears!” he would squeal as if to invite his forgetful young opponent to remember what came next.

Some just wanted centre stage and a set piece and a couple in point are Adrian Street Esquire whiled away a few minutes of every first round by having a flex, and Goldbelt Maxine would indulge himself for endless minutes with the unspectacular and allegedly controversial sawing motion across the throat. We were not impressed.

We conclude with a move at the very heart of professional wrestling, the magnificently and evocatively named Boston Crab. Almost an embarrassment to the game by dint of its inescapability, particularly when enforced by masters of the art such as Bert Assirati and Alan Garfield. A whole array of spectacular let outs and crawl throughs developed, in some cases rather unbelievably. More intriguing is the poor relation, the Single Leg Boston. The instant utility move for when things go awry, plus, just look how frequently it was used.

Have you noticed anything?

Whenever an unathletic ageing villain like, McManus or Peter Kaye, was being outwrestled and a fall down, the youthful hero would fall badly and succumb to two quick SLBs.

16411