With thanks to Rodney Challis, Simon Coward, Jimmy Devlin, Don Robinson, Eddie Rose.

Wrestling Heritage welcomes memories, further information and corrections.

As the time approached 10.15pm, just after Perry Mason had astonishingly won yet another apparently hopeless case, the BBC1 continuity announcer informed viewers that the following programme would be professional wrestling from the Sports Stadium, Brighton, an historic wrestling venue that had witnessed Lou Thesz defending his World Championship against Bill Verna a few years earlier.

Until that moment ITV and Joint Promotions had been the enclave of televised wrestling. With both Joint Promotions and independent television companies keen to protect the public image of wrestling as a competitive sport viewers were familiar with highly regulated shows that were far less exciting and much more predictable than the wrestling that could be seen live in the halls of Britain.

The first national broadcast on the BBC offered the tantalising prospect of the beginning of a challenge to the dominance of ITV and Joint Promotions that would have changed professional wrestling for years to come.

Within seconds of wrestling going over to “the other side” it was clear that the BBC had fewer inhibitions about the reputation of professional wrestling than their commericial rivals. Unlike ITV the BBC show was produced by the light entertainment department and not BBC sports. Nevertheless, Eddie Waring was enlisted to provide an irreverent commentary from the perspective of a respected sports commentator.

Those who saw the broadcast on their 19” black and white televisions remember that the more effective use of microphones around the hall improved the atmosphere in their living rooms and gave the programme more of a “live” feeling than the ITV shows. Mind you, with more than 4,000 fans packed into the huge stadium there were enough present to make a lot of noise.

The wrestling itself was of a much rougher nature than what was normally seen on television and viewers recall abuse of the referee, something that would never have been allowed on ITV.

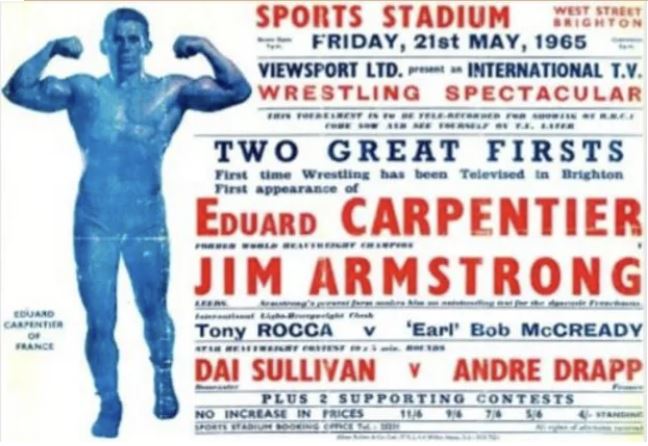

Three bouts were broadcast over the following forty five minutes. The tempestuous Doncaster heavyweight Dai Sullivan faced the French wrestler Andre Drapp and in the main event Leeds heavyweight Jim Armstrong faced the former world heavyweight champion Eduard Carpentier. The third contest, the one which displayed the technical skills of the wrestlers, matched Sullivan’s son, Earl McCready, with Londoner Tony Rocca. Two more matches, that were not broadcast, Peter Kelly with Tony Granzi and Chris Harris with Abe Goldstein.

The programme ended at 11.00pm, just in time for the news headlines. Suggestions made at the time that the end of the contest had been conveniently arranged in time for the news were nonsense as the matches had been recorded the previous Friday.

The programme was unheralded by the BBC, almost as if they were embarrassed the sport was tarnishing its schedules. There was no advance publicity in the Radio Times, just the programme listing that promised, “A gala evening of all-star professional wrestling from the Sports Stadium, Brighton.”

Nevertheless, it does seem to have been well received by viewers, and two weeks later the Radio Times published a letter from Fred Bragg of Cumbria, “I feel I must write and offer a sincere ‘three cheers’ to BBC1 for giving us a programme of wrestling which has been long overdue. I’m sure I speak for others when I say please give us more.”

We have been assured by the BBC that no recordings of this historic event have survived. The involvement of Jarvis Astaire’s View Sport and overseas broadcast rights gives faint hope that one day a recording may surface.

Although this was the first time wrestling had been broadcast nationally by the BBC the national broadcaster was not entirely a novice in such matters. A few months earlier, on Monday 4th January BBC2 had broadcast professional wrestling from Southend. That show had gone largely unnoticed as BBC2 was only available in London, the South East and Birmingham to those who had invested in a new aerial and dual standard television set that could receive the new station broadcast on UHF 625 lines.

Scarborough promoter Don Robinson was the man honoured with matchmaking and promoting the Southend show. Broadcast at an earlier time of 7.00pm the BBC promised, “An international competition of all-star wrestling from the Cliffs Pavilion, Southend, where some of Britain’s leading wrestlers top the bill in a gala charity performance.”

Commentary was by Eddie Waring and Mike Marino faced “Harlem” Jimmy Brown in the main event of the fund raising show for the Variety Club of Great Britain. Also on the bill were Dai Sullivan, Gori Ed Mangotitch, Judo Al Hayes and Jimmy Devlin.

Jimmy Devlin remembers the day well, “We all thought this could be the start of something big, and that we would not look back. I was on with Milton Clarke, and I remember we got very good money for the match. Normally I would get £5 a match but for the BBC show I was paid 21 guineas (£22.05) ”

Unknown to viewers, and BBC executives, was that the BBC 1 Brighton show itself almost never took place. Behind the scenes was a tussle of two business giants greater than anything we might have seen in the ring.

Following the success of the Southend show Don Robinson had high hopes that the BBC would award his company the rights to promote future shows for transmission. Robinson was the most successful of the northern independent promoters having presented shows at more than thirty venues including the huge Nottingham Ice Rink; Queens Hall, Leeds; and Edinburgh Ice Stadium. Headquartered in Westminster Bank Chambers, Scarborough, the company had recently expanded their promotional businesses into the south and shared the offices of Paul Lincoln Management in Old Compton Street, London.

It was a massive shock to Robinson when one of his wrestlers, Dai Sullivan, told him of a telegram he had received from Jarvis Astaire asking him to take part in a show he was promoting at Brighton for the BBC. Astaire was an entrepreneur with a vision of broadcasting closed circuit events around the world. He had already begun to develop a business portfolio that included wrestling promoting as a vehicle for his broadcasting ambitions and had many influential contacts in broadcasting and entertainment spheres.

Robinson advised Sullivan and the other wrestlers to telegram their agreement to appear for Astaire; believing that a telegram would not be accepted as evidence in any legal proceedings that might follow.

On Friday 21st May, 1965, Robinson and the northern wrestlers billed to appear travelled to London and the offices of Jarvis Astaire. A blunt exchange of views took place in Astaire’s office in which the Yorkshireman told Astaire the wrestlers would not be working for him that night. Astaire threatened legal action in return.

The discussions were at a stalemate until the moment Robinson told Astaire a group of wrestlers, including main eventer Jim Armstrong, were sitting in his car ready to return home and the telegrammed agreement to appear would hold no weight in court.

Astaire’s response to the northern promoter’s bravado was the moment that Robinson acquired a life-long admiration and respect for the more experienced business man he was facing.

Astaire, visibly shaken according to Robinson, remained completely in control of the situation and quietly suggested a break for coffee and sandwiches.

When the discussions resumed the atmosphere was completely different. Again he quietly assumed control and Jarvis Astaire calmly proposed that a positive solution be found to the impasse. An astute and experienced business man himself Don Robinson had already planned for this scenario; why else would he have brought the wrestlers with him had he not planned to strike a deal?

Robinson proposed that the Brighton bill went ahead as planned, with Astaire promoting, but that the two of them agreed to form a joint company to promote future BBC shows should the opportunity arise. Hands were shaken and a deal was done.

“Jarvis Astaire is one of the hardest, but one of the most honest and friendliest of men I have ever met,” Don Robinson told Wrestling Heritage.

Following the deal between the two business men they travelled together from Astaire’s office to Brighton for the evenings wrestling. Don Robinson continued, “It was a life changing day. I considered myself a successful business man, but this was the first time I had been in a real executive board room. It was the first time I had travelled in a Rolls Royce. Later in life I would travel in lots of Rolls Royce’s, helicopters, aeroplanes, and meet incredible people, but Jarvis Astaire changed my life. He’s a fantastic man.”

Wrestling fans hoping that the BBC’s interest in the sport would continue and provide an alternative source of wrestling entertainment were to be disappointed as the national broadcaster declared a lack of space in the schedules for further events.

The disappointment of the independent promoters, particularly those best placed to take advantage of the situation such as Paul Lincoln and Don Robinson, must have been even greater as they saw the opportunity of lucrative contracts fade away. For Lincoln, in particular, it was a severe blow as four years earlier discussions between the Lincoln organisation and independent television executives had reached their final stages before ITV made a last minute decision to award the evening mid week session of televised wrestling to Joint Promotions who were the incumbents of the Saturday programme.

In the six or seven years previous Paul Lincoln had become a very strong rival to the huge Dale Martin organisation that controlled most of the Joint Promotion shows throughout the south. The disappointment for Paul Lincoln was a significant factor in his decision to allow the larger Dale Martin Promotions take a controlling interest in Paul Lincoln Promotions just a few months later. With a television contract of his own Lincoln would have been unlikely to take a back seat by relinquishing control of his expanding company.

The disappointment was equally great for Don Robinson as his co-operation with Jarvis Astaire would have made them a formidable force in British wrestling that would undoubtedly have changed the wrestling landscape for years to come.

Despite rapidly withdrawing from televised wrestling tournaments the BBC continued to show an interest in professional wrestling.

The following year, hidden away late one Saturday night on 13th August 1966 they broadcast the French-Canadian documentary “The Wrestlers.” The 11.20pm start time probably ensured that this highly acclaimed film produced by the National Film Board of Canada, went un-noticed by most viewers. The documentary promised “A candid view of the all-in wrestling game in Canada,” and followed the fortunes of a group of Montreal based wrestlers. The programme centred around a tag match in which Edouard Carpentier and Dominic DeNucci faced the Kangaroos.

Attempting to analyse the motives of the near hysterical fans the narrator concluded (hardly surprisingly) that they were not there to witness athletic prowess, “They have come to an arena where they hope to see wickedness get its just deserts, to see evil (personified by the hateful Kangaroos) banished and humiliated.”

The pace was more sedantry and thankfully less analytical six years later when the BBC documentary series, “The Philpott File,” devoted an entire programme to the life and career of the Klondyke Brothers. It was remarkable that the BBC dedicated the best part of an hours peak time viewing to a sport they did not televise, and two participants known only to fans of the independent promoters.

The programme included action footage from an Orig Williams show and extensive interviews with Williams, the Klondykes and Klondyke Bill’s mother. Whilst undoubtedly raising the profile of the Klondyke brothers the programme did nothing to enhance the Klondykes’ monstrous image with Bill’s mother describing him as “..a really lovable, cuddly toy,” and the wrestler berated by his girlfriend for his reluctance in sorting out their wedding plans.

In 1992 the BBC Arena documentary series promised to “..get behind the mask of wrestler Kendo Nagasaki.” TV Producer Paul Yates fulfilled the ambition of artist Peter Blake to not only meet Kendo Nagasaki but also paint his portrait. It was a highly dramatic, at times verging on silly, documentary that preserved and enhanced the Nagasaki image as Blake pursued the wrestler.

Eddie Rose recalled his involvement in a BBC programme called “So You Want To Be A Wrestler.” The programme was filmed at the Manchester YMCA following the fledgling career of Ray Glendenning. Also featured in the programme were Ezra Francis, Tommy Mann, Jimmy Savile and the gloriously named Tiny Greenhills.

Other occasions when the BBC has recognised the importance of wrestling as part of Britain’s social landscape have included The Big Time, in which a school teacher was trained in the ways of professional wrestling before getting his come-uppance at the hands of John Naylor at the Royal Albert Hall. In 1989 “Forty Minutes” included a programme called “Raging Belles,” documenting Klondyke Kate’s match with Nicky Munroe.

BBC radio has also played its part. In 2005 Hungarian poet George Szirtes told the story of wrestler Tibor Szakacs, whom he had first met in 1956 after they had both arrived in Britain having fled the Hungarian uprising.

Wrestling Heritage member Rodney Challis devised and researched a BBC Radio 4 documentary, “Not a Night for the Squeamish” in 1984. The programme was recorded at live wrestling shows in Sale and Liverpool, both of them Brixon Dixon Wrestling Enterprises shows featuring Ray Crawley, Monty Swann, Steve Peacock and Klondyke Kate.

Incredibly we have to go back much further in history to uncover the BBC’s initial relationship with wrestling. Whilst most authorities name Ken Johnstone, Head of Sport for Associated-Rediffusion as the man who introduced wrestling to Britain’s television viewers in 1955, others had gone before him.

The BBC had begun scheduled television broadcasts from Alexandra Palace in London on 2 November 1936. To begin with only a few hundred viewers had the necessary receiving equipment, and less than three years later when the service was suspended due to the outbreak of war less than 40,000 homes could receive programmes broadcast for only a few hours each day.

BBC television broadcast their first wrestling match, they called it catch-as-catch-can on 12th March, 1938, describing it as a form of fighting mid-way in violence between all-in wrestling and ju-jitsu.

The exhibition match was between the Canadian Earl McCready (not the one who appeared in Brighton later) and the South African Percy Foster. For the record the commentator was Emil Voight, who had competed in the 1904 Olympics as an athlete and some four years earlier had authored “Modern Wrestling Holds.” The referee of the contest was K.J. Staunton. Voight and Staunton were to become regular officials of the BBC contests.

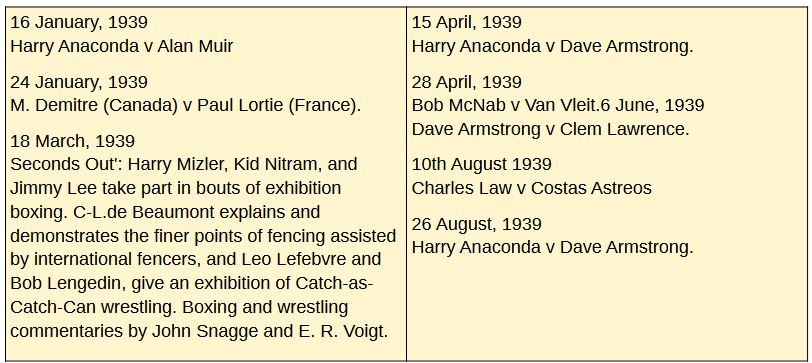

Wrestling returned to the BBC six weeks later, with McCready this time facing Harry Anaconda, and was then set to become a regular twenty minute feature for the remainder of the year and in to 1939.

In July 1938 BBC Radio broadcast the British Empire Heavyweight Championship contest between Earl McCready and Tim Estelle from the Holborn Stadium.

Apart from Anaconda and McCready other names familiar to Wrestling Heritage readers that appeared on the BBC before the outbreak of war included Londoner Chick Knight, Mike Demetrie, Dave Armstrong, and Clem Lawrence.

Wrestling continued throughout 1939 until within a few days of the outbreak of war and closure of BBC television. The final exhibition match, broadcast on 28th August, was between Harry Anaconda and Dave Amstrong. On 1st September, 1939, the television service closed abruptly whilst showing a Micky Mouse cartoon depriving viewers of their scheduled dose of wrestling the following day. The bitter pill was sweetened by a radio feature in “Talk On Sport” in which Count V.C. Hollander talked about the revival of catch-as-catch-can. Most people would have had more pressing matters on 2nd September, 1939.

Following the end of the war BBC television resumed on 7th June, 1946, and just three days later Harry Anaconda faced Bert Assirati, with Emil Voight once again commentating.

During the months that followed many wrestlers familiar to Wrestling Heritage readers made their television debut, amongst them Charlie Green, George (The Farmer) Broadfield, Dick the Dormouse, ‘Chick’ Elliot, Tony Baer, Ted Beresford, Charlie (College Boy) Law, Ron Harrison, Stan Stone, Jack Dale, Charlie Fisher, ‘Sonny’ Wallis , Flash Barker, Joe Hill, Vic Coleman, Pat Kloke, Bob Archer O’Brien and Kid Pitman.

One more name. On 26th May, 1947, Al Lipman faced a young Londoner with the name of Mick McManus. No one would have forecast that young man’s future.

In August and September of 1947 the BBC also broadcast a programme called “I Want to Be a Wrestler,” in which presenter McDonald Hobley received lessons from wrestlers Vic Coleman, Johnny Lipman and Saxon Elliott.

On 28th June, 1947 a contest between Kid Pitman and Johnny Lipman is the last that we can find recorded until the mid 1960s.

So despite common perceptions there has been a long history of wrestling “on the other side.” Alas, it all amounts to no more than eighty years of flirting with the BBC never willing to make that final commitment.